From Pipeline Fillers to Platform Plays

Yesterday morning, AbbVie dropped a $2.1 billion headline - announcing it will buy Capstan Therapeutics and, with it, a pre-clinical in-vivo CAR-T “toolkit” capable of re-programming immune cells inside the body. The deal isn’t about slotting a single late-stage asset into AbbVie’s post-Humira pipeline; it’s about owning the full technology operating system comprising Capstan’s targeted LNP delivery and its programmable mRNA payloads when combined can spin out dozens of future programs.

Yesterday’s news is the latest, and loudest, data-point in a year-long pattern: Lilly’s base-editing buyout of Verve, BMS’s prime-editing pact with Prime Medicine, and now AbbVie’s Capstan swoop all signal that Big Pharma’s shopping cart has moved from finished goods to modular tech stacks. In this Lonrú Lens post, we’ll unpack why platform control is eclipsing asset acquisition, how in-vivo versus ex-vivo strategies are reshaping CMC and analytics demands, and, most importantly, what this shift means for companies supplying the “picks and shovels” of cell-and-gene-therapy (CGT) manufacturing and quality. Expect a deep dive into the new M&A economics, the tooling gaps Big Pharma just inherited, and the strategic plays that CGT enablers should make before the next billion-dollar platform changes hands.

Why the pivot?

Patent-cliff paranoia: With blockbusters like Humira already off-patent, acquirers are chasing engines that can feed multiple franchises, not one-shot drugs.

CapEx vs Build-time: Buying a fully formed editing or delivery “OS” leap-frogs the 5-7 year slog of internal development.

Competitive moats shift upstream: If editing fidelity, delivery tropism or CMC automation become the differentiators, owning the platform locks competitors out of entire modality classes.

What a platform deal looks like in practice

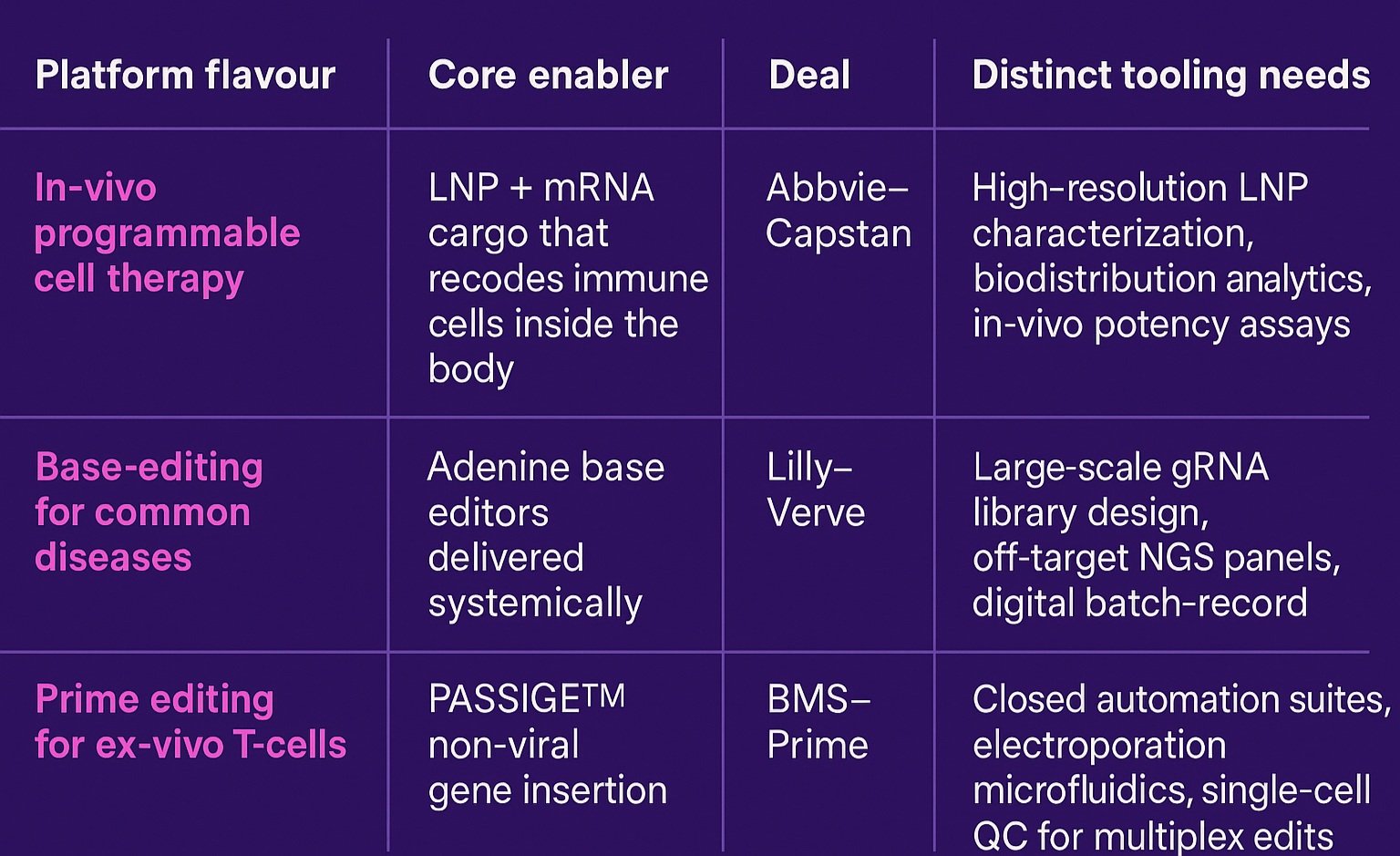

The three deals in focus that have re-framed 2024-25 M&A illustrate just how differently “platform” can look in practice, and why the supporting tool chain must be equally diverse. AbbVie’s buy-in to Capstan gives it an in-vivo programmable-cell platform, where targeted lipid-nanoparticle (LNP) composition and real-time bio-distribution analytics are the gatekeepers of potency and safety. Lilly’s takeover of Verve centres on systemic base-editing, a population-scale play that makes high-throughput gRNA library design, on/off-target NGS panels and seamless digital batch-records non-negotiable. Bristol Myers Squibb’s alliance with Prime Medicine, meanwhile, is rooted in ex-vivo prime editing, pushing the need for closed, automated cell engineering suites and single-cell QC to handle multiplex edits at commercial scale. Read together, the deals prove that Big Pharma isn’t just buying optionality; it’s inheriting distinct, capital-intensive tooling gaps. In the next section we explore how specialised CGT vendors can turn those gaps into growth.

One size doesn’t fit all: each CGT platform archetype carries its own toolbox.

The ripple-effect for CGT tool providers

For companies that make the “picks and shovels” of cell-and-gene manufacturing, the new platform land-grab translates into a race for capacity, data fluency and regulatory credibility, simultaneously. Big Pharma’s acquisition teams have bought themselves ambitious editing blueprints, but they did not buy the supply-chain depth, digital infrastructure or quality modules needed to run those blueprints at scale. That shortfall thrusts specialised vendors into a more strategic role: LNP-analytics firms are being invited to embed directly into CMC work-streams; cloud-native e-batch-record providers are negotiating multi-asset master service agreements; microfluidic-hardware players are fielding requests for closed, GMP-ready pods that can be dropped into established manufacturing plants. In other words, tooling companies are no longer peripheral suppliers instead, they are fast becoming co-architects of the very platforms Big Pharma just paid billions to control. The winners will be those that can plug gaps today while designing modular solutions that won’t bottleneck the multi-indication pipelines these deals aim to unlock in the next five to ten years.

Three emerging CGT platform engines: in-vivo programmable cell therapy, systemic base editing and ex-vivo prime editing - ready to power a decade of multi-asset pipelines.

Strategic plays for tooling companies

To capture the white-space that Big Pharma’s platform buys have opened, CGT tool providers will need to stop thinking like commodity suppliers and start behaving like platform accelerators. The first step is commercial: price your offering against the value it unlocks across an entire multi-programme stack, not on a per-lot consumable basis. Next comes product architecture - design every module to plug seamlessly into either an in-vivo or ex-vivo workflow, because sponsors may soon straddle both. Data is the third pillar: milestone-heavy deals shift technical risk onto development partners, so the vendor that can surface lot-to-lot reproducibility, predictive release analytics and audit-ready batch records becomes indispensable. Finally, rethink deal structures altogether; in a world where the tool can determine whether dozens of assets reach the clinic, equity, royalties or shared IP could be worth more than a traditional supply contract.

Bottom line

Pipeline filler M&A is giving way to platform play M&A. For CGT tool providers, that means the next wave of growth will come from positioning your technology as critical infrastructure for these newly acquired operating systems. The winners will be those who can scale, standardise and data-enable the platforms that Big Pharma just paid billions to own.

Lonrú Lens will continue to track how these platform deals reshape the CGT value chain - and where enabling technology companies can capture value in 2026 and beyond.